Immolation begins with burning—a world burnt to the ground, ashes still smouldering and a revolutionary basking in the glory of his victory. Immediately, the victory is marred with infighting and corruption.

Director Pam Patel and the cast members of Immolation presented an anthology with some amazing moments. But the play was not connected to its name—it gave insights into freedom on both a personal and a societal level but did not address the sacrifice and protest integral to the idea of immolation.

Immolation is a deeply powerful and empathetic form of protest. It is the most violent non-violent protest.

Immolation comes from the Latin immolatio, which meant sacrifice or offering.

To immolate oneself is to say: “others are suffering, you’re not watching, so I will make myself suffer so you cannot avert your eyes”. It is an expression of pain so deep-rooted in either yourself or another, that you not only end your physical existence but make it excruciating for yourself.

This form of protest has a long history behind it. In India, women would set themselves on fire to protect their honour in a practice known as jauhar. In Iran, people have used immolation to protest censorship and the compulsory hijab policy. In Pakistan, Bishop John Joseph immolated himself to protest blasphemy laws. In 1963, Thích Quảng Đức protested the Buddhist Crisis in Vietnam with his self-immolation. In February, Aaron Bushnell immolated himself for Palestine—he was not the first.

Immolation is loaded, it is heavy, it is sacrifice, it is destruction. It demands people watch and pay attention.

It is not represented in this play.

While it could be argued that activists being hanged in the background of some of the scenes is also a form of sacrifice, it is a tenuous connection. Instead, the play is more focused on freedom in its many forms—both on a micro and a macro level.

It excels more in the stories of personal and domestic spheres. The scenes of the family dinner and between the two transgender characters are poignant explorations of freedom of the self, but the scenes of the revolution and the family picnic take on too large topics to make any major points about their topics.

The cast conveyed stellar performances in both the scripted and the improvised sections. Jaime Borromeo has a booming voice which enhances his performance first as the leader of the Bring Us Revolution Now! Movement and then as the father in a nuclear family of five.

As the revolutionary and his second-in-command argue about who should be martyred and how, the tone is set for the rest of the play. Immolation is an honest and earnest depiction of the illusions we maintain for ourselves and the cost we, as a society, pay for them.

In the first act, a family has dinner. This scene is powerful, it conveys the exhaustion of the mother who, in her silence and then in her rage when her hard-made meal is destroyed. Although he falters for a moment when the mother’s silence becomes a scream, it is ultimately the father that holds the power and the golf club which he aims at the mother’s head. Even in her anger, she loses. The youngest is ignored.

This scene is also one where there is considerable improvisation. While the fight is planned, the reason is always different. At the end of the scene, the narrator goes feral, but the reason is different each time. However, when the narrator becomes feral, the scene falls apart. The connection between the family’s story and the narrator’s loss of sanity is unclear.

In the fall, a family has a picnic in a park with two bodies hanging behind them. As they neurotically uphold the picture of a happy family, an activist comes onstage and graffities the rocks in the area. The parents, shocked, try to do damage control while their son is inspired. The activist is arrested and hanged in the background.

In the winter, a woman, June Sung, steps on stage, strips, and plays in the snow. This scene was, in my opinion, the most powerful and well-choreographed. It showed a transgender person experiencing joy in their body. Then, as they hear other people walking by, they hide and observe with the audience.

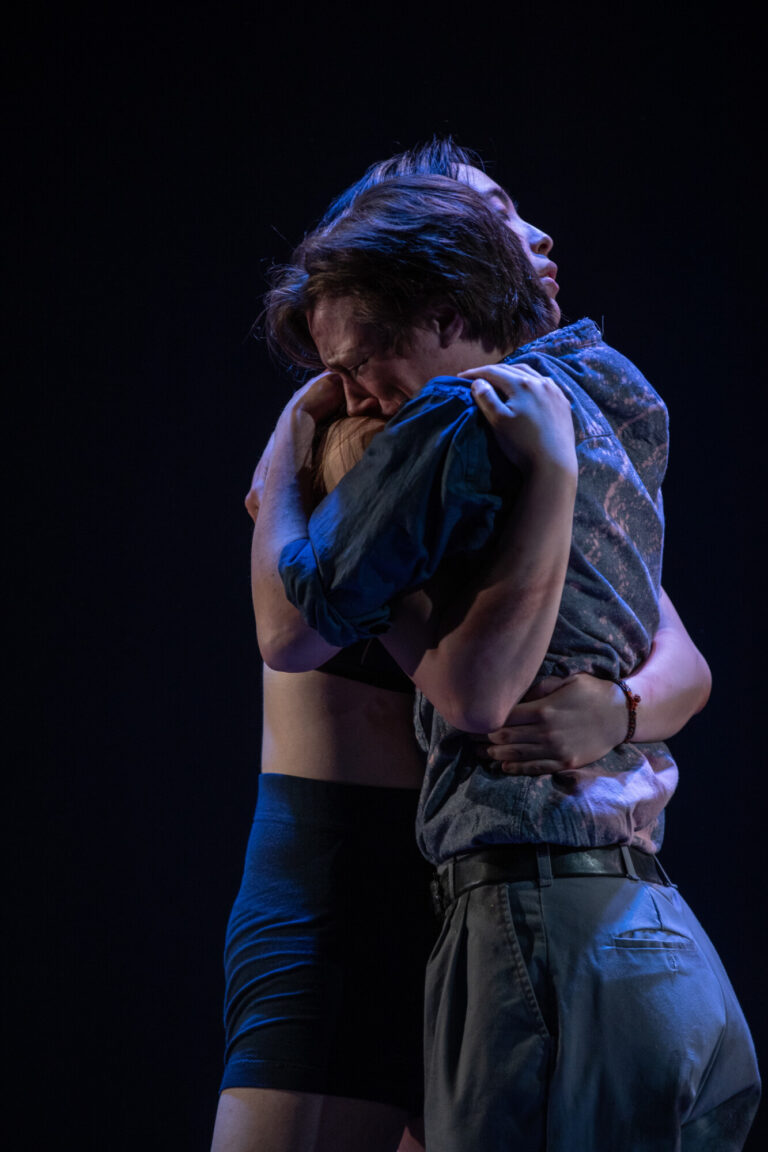

The other person, portrayed by Quinn Andres, is facing their own inner demons—as they are walking, others are perceiving them, glaring them down, calling them a coward. When they come to centre stage and Sung’s character addresses them, they are hesitant to turn and face her. Sung’s character, although more confident, is still hesitant to allow Andres’ character to turn and see her. Andres’ character still asks permission first.

Sung and Andres perfectly portray the intimacy of merely being seen as you are. While Sung is on stage in her underclothes, Andres’ character clings to their coat and clothes. They reach toward each other, gently and hesitantly touch their fingers and then—suddenly overwhelmed—Andres runs to Sung and they share a long and tight embrace.

The actors’ body language was immaculate—Andres went from walking among the background characters confidently, then very paranoid. And then, with Sung, they morph their body into a more “feminine” presentation. Sung, on the other hand, goes from hesitantly stripping, then joy, then hesitation as she reaches out to Andres, then supporting them. What stuck with me was her leaning forward and catching Andres—holding the weight is a difficult task, but she held a facial expression of gentle acceptance and empathy while also physically supporting Andres. Without speaking, Sung said, “it’s okay, I know”.

The final act was that of an activist, portrayed by Iman Yousefi, as she undoes her shackles. Nika Ghorbani is in the background, providing encouragement and support, pushing Yousefi’s character to break free. The image of Ghorbani in the background, Yousefi imploring the audience from centre-stage and the rest of the cast facing the audience is striking.

The anthology wraps back around to summer, with Borromeo’s character leading a victorious revolution.

The cyclical nature is clear, but its relevance to the stories is unclear. Still, the cast and the stories carry enough weight on their own to make the play a worthwhile experience