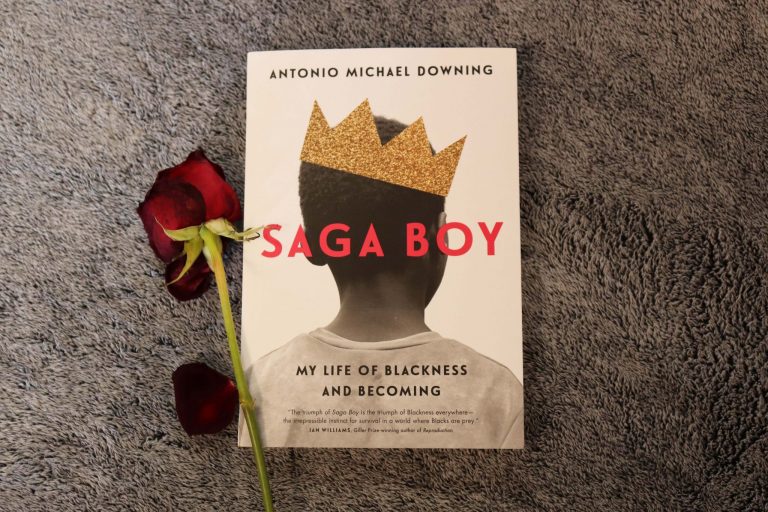

Saga Boy by local author Antonio Michael Downing starts off with a loss. As the memoir progresses; however, readers gain an abundance of insight and thoughtfulness after taking in this delight of a novel. As Downing tries to escape his family, culture and past, he creates three musical personalities: Mic Dainjah, a punk rapper; John Orpheus, a sequinned, leather-clad pop star; and Molasses, a soul music crooner.

Downing takes readers through his life as a Black man who moved to Canada from Trinidad with solemn prose. His family’s migration follows shortly after the loss of his grandmother when he was 11 years old. Downing’s gripping memoir consistently toes the line between myth and fact, sad and sweet, and leaves his readers wanting more.

This book offers something for everyone. For immigrants, it weaves a familiar tale of having to leave behind your home and create it somewhere new. For second-generation Canadians, it portrays the joys and struggles of being a person of colour in Canadian society. Through his expert and startling mash-up of memory recounting, the novel begs the question: what does it really mean to be Canadian?

Downing makes intelligent use of code-switching from Trinidadian vernacular to Canadian English. This creates a seamless transition from one location to the next, in stark contrast to the author’s actual lived experience. The way he moves from his life in the lush forest of Southern Trinidad to Wabigoon, Canada creates a feeling of cultural whiplash. In this way, he replicates his life story.

Much like many immigrants and their children, life stories are shared through food. Diasporic people can’t help but feel a warm and fuzzy feeling when Downing talks about the food from his childhood. There is a sense of familiarity in the way he relates food with memory. Doubles and pakoras feel like universal comfort food to which readers can turn. Downing has an innate openness to him as an author that makes his audience want to get to know him.

Readers of Saga Boy are also treated with colourful retellings of Downing’s family mixed with Trinidadian folklore and urban legend. It makes the book feel like a fairy tale brought into the grim lens of reality. Downing talks about traditional mythology coexisting with Christianity, a phenomenon that affected him greatly in Canada. When his family faced hardships, spirituality and faith seemed to be used as an escape from the darkness of the world.

His musings on colonization and its everlasting impact on many of the world’s peoples is enough to bring tears to the eyes of the diaspora. Downing grapples with the attempted erasure of his culture and peoples. The novel’s tone is honest and somber, with a lot of heart and soul poured into every sentence. Saga Boy also explores what it means to be a Black man. Toxic masculinity has become a hot-button topic with the rise of the “alpha male” mentality. Downing brings the Black male perspective into the discussion and takes a look at manhood from a critical standpoint. For example, he talks about his grandfather whom he only knew through pictures of him hung on the walls. His grandfather was a “Saga Boy,” a West Indian playboy who was luxurious for luxury’s sake. Despite Downing’s attempts to distance himself from his family legacy, the reader slowly comes to realize that Downing becomes a Saga Boy himself when he comes of age. The novel chronicles his journey from young boy to man in a matter of 300 pages.