As bodies keep mounting from the ongoing drug poisoning crisis and pandemic, a new group is stepping up to provide much-needed support for outreach workers and to remember the lives lost.

Years of illicit-drug toxicity deaths, rising rates of homelessness and the COVID-19 pandemic have put an untenable strain on frontline workers and social service agencies across Canada. In Waterloo Region, Peregrine Outreach has emerged in response to these issues—a worker-led initiative that supports outreach staff in the region.

Three members of Peregrine Outreach—Sara Escobar, Sharon Hartigan and Irene O’Toole—met me at a small restaurant tucked behind a deli on the corner of Courtland and Benton. The idea for Peregrine percolated for years, and was developed in close consultation with local outreach workers before it was launched in spring 2022.

Peregrine’s first offering was a series of psycho-educational support group meetings. Participants focused on issues and topics relevant to their work, and all the discussions were facilitated through a trauma-informed lens.

One vital issue identified by outreach workers was the loss of rituals to grieve, mourn and celebrate lives taken by the drug poisoning crisis and pandemic. Hartigan pulled out a large blue binder to illustrate one such ritual Peregrine maintains. It was filled with hundreds of photographs and eulogies of people who had been supported through outreach efforts over the years.

“This is just the second volume,” Hartigan said.

I listened quietly while flipping through their binder, faintly recognizing faces I might have seen at Queen Street Commons or Willow River Park.

“These people were loved and not loved,” Hartigan said.

“Embracing unconditionally where they were in their journey just gave us that ability to learn more about humanity.”

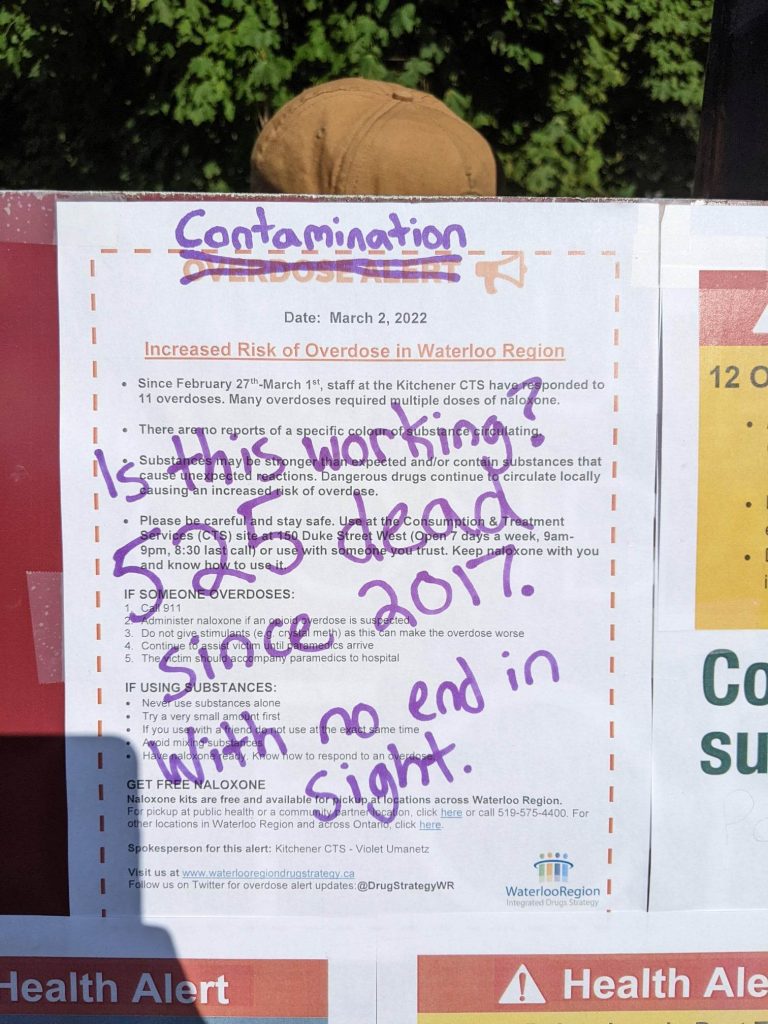

According to the office of Ontario’s Chief Coroner, between 2018 and 2022 there were 519 fatal drug poisoning deaths in Waterloo Region, and an average of ten deaths every month since the start of 2022.

Unlike other first responders who experience brief encounters with people who overdose from drug poisoning, outreach workers like Escobar and Hartigan spend months and sometimes years developing relationships with these individuals.

“When you’re working in that space and connected to people, their loss hurts,” Escobar said.

“It’s more than just trauma, it’s spiritual pain.”

To better recognize and address this pain and grief, Peregrine has partnered with Crow Shield Lodge to host monthly memorials at their site just outside New Hamburg.

Escobar emphasized that Peregrine is dedicated to continuing these memorials.

”Forgetting people in death just doesn’t seem right,” she said.

Although some local agencies do organize dedication and memorial services and provide transportation to funerals, Escobar argued that Peregrine’s rituals are more accessible and responsive to outreach workers’ needs because of the trust and experiences they share with their colleagues.

“Frontline workers have always acknowledged that their agencies can only do so much to support them in dealing with this grief,” Escobar explained.

The inadequacy of supports from agencies is in large part a consequence of Ontario’s decades-long neoliberal austerity which gutted social funding and drove organizations to adopt a profit-driven philosophy called new public management. This approach relies on corporate management techniques, such as regular performance evaluations, to find areas where they can cut costs and increase efficiency.

Escobar said that the kind of social, emotional and spiritual help that outreach workers value and provide for each other is not easily measured, and thus not budgeted for or appreciated by managers.

“It’s really hard to report on,” Escobar said.

“It’s about sharing stories of how people are feeling and what they need. And those are really hard things to put into stats, so funders are not huge on that.”

Michael Parkinson, a Drug Strategies Specialist and prominent harm reduction advocate in Kitchener, remembered when he and others who addressed drug-related issues across Ontario went to the Ministry of Health to advocate for increased supports for direct service workers in 2016.

“We told them there’s a tidal wave of death that has landed and is not going away soon enough for anyone. People will burn out,” Parkinson said.

The ministry responded that it was ultimately up to each individual agency to figure out how to protect the mental health and well-being of their employees on the frontlines.

Jessica Bondy, director of housing services at House of Friendship, said that her organization, like others, offers mandatory training around psychological health and safety for all of their employees.

Whether people are responding to overdoses or hearing the heartbreak of someone’s previous trauma or adverse childhood experiences, Bondy said that House of Friendship tries its best to support people in understanding the whole magnitude of that work.

“One of the big things we do is we provide the opportunity for folks to understand things like burnout and understand the difficulties and challenges tied to this work,” Bondy said.

“We’ve also implemented a boundaries policy to support our teammates in understanding those professional boundaries and lines which are really key for folks,” she said.

Legislation demarcates the therapeutic and mental health supports employers must offer outreach workers. However, Parkinson noted that when governments do move to mandate supports for outreach work and workers, it often does not align with what the needs are on the ground.

Escobar agreed that this misalignment rang true for her and others; while agencies do provide enough support to meet legal requirements, they tend not to encourage deeper, more relational care between outreach workers.

“That’s perhaps why we see these watered down, hyper-professionalized programs and supports which don’t have great value to the people they purport to serve,” Parkinson said.

Parkinson argued that to truly relieve outreach workers, every level of government needed to invest funding in prevention services.

“If they were to fund psychosocial support or things like housing, turning this drug poisoning crisis around, eliminating criminalization…those are the things that would help make a difference in people’s lives and in the lives of direct service workers.”

Michael Brown, a PhD student with over 15 years of outreach experience, shared that Peregrine also creates room for outreach workers to reflect on the structural and interconnected issues fueling the crises their community faces.

“I don’t think we realize it but we’re living in the ruins of capitalism right now, and it’s a global catastrophe,” Brown said.

“It’s traumatic and we don’t know what to do. I just need to be able to say, outside of the workplace, that I’m seeing this reality and it’s awful for the people that I’m supporting.”

As outreach workers continue to help clients navigate complex, harmful systems, they will find solace in Peregrine’s responsive supports and rituals—and by carving out space for grief, connections, and healing, Peregrine demonstrates how we can all build more caring and intentional communities.