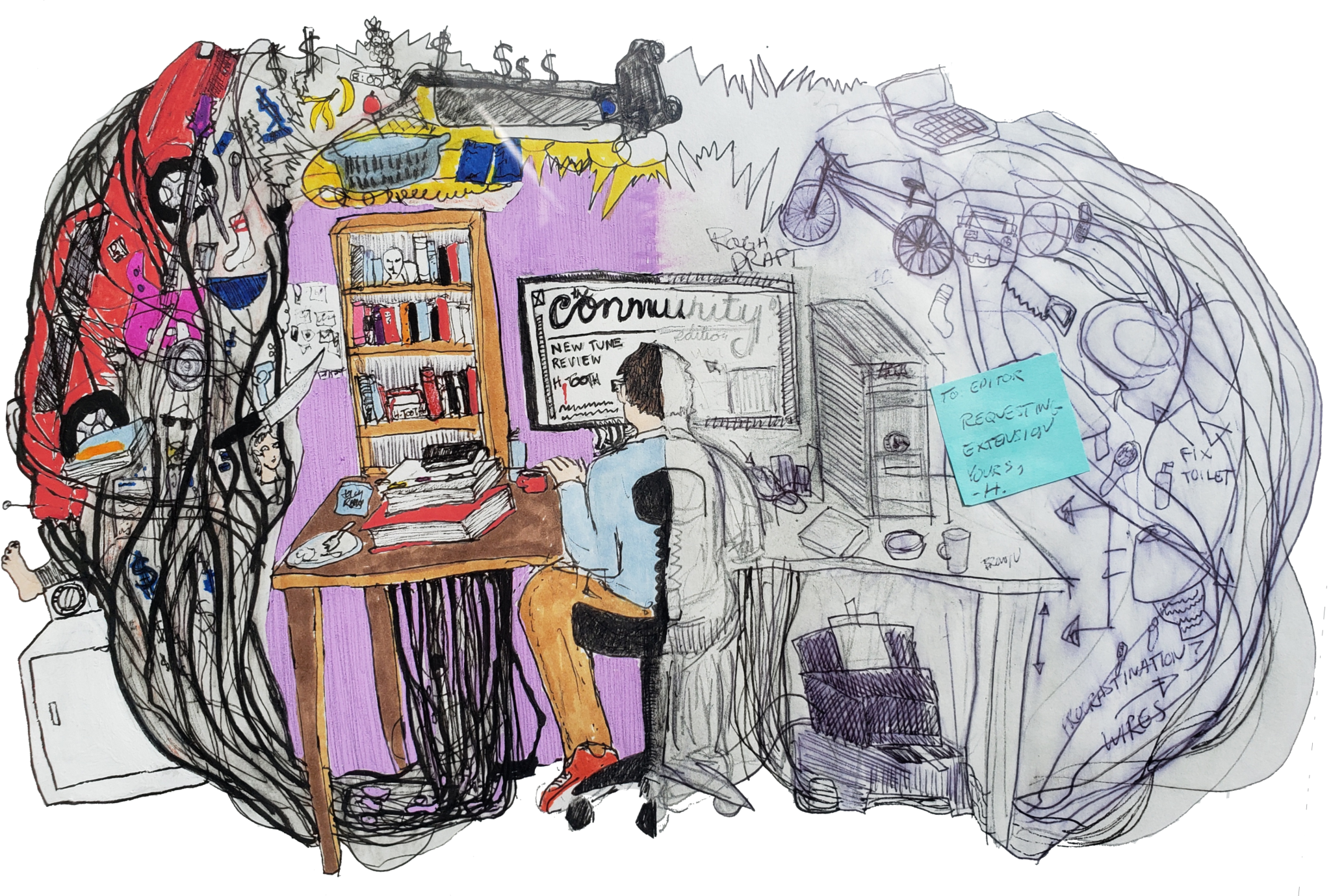

Last month, I sent an email stringing together excuses and begging forgiveness for not getting my work in on time. I did have valid reasons, but something I am pained to admit to is that one of my major issues was procrastination.

I am not alone in this. “The nature of procrastination: a meta-analysis and theoretical review of quintessential self-regulatory failure” by P. Steel concluded that chronic procrastination affects up to 20 per cent of the adult population, while other studies report more than 50 per cent of respondents find themselves procrastinating from time to time.

Procrastination can put us in weird places. As we become aware of our procrastination, we might try to focus and then find suddenly we are back on social media scrolling, or watching just one more YouTube video or, in my case, cleaning dishes because “I cannot work with dirty dishes in the sink!”. Then we suddenly find we haven’t completed the task we needed to and it’s now time for bed. We might wake up dreading the morning because that task is there waiting for us.

So, why do we procrastinate? Our culture tells us procrastination is an issue of being weak-willed or unfocused, and that to deal with it, we must just buckle down and do the task. However, the realities of procrastination have very little to do with being weak-willed and a lot more to do with our brains’ coping mechanisms when faced with stress or boredom.

Studies show that at first procrastination starts because of boredom, we’re having to do a task that we don’t want to do and so we start to take little breaks, or we schedule the task for some later time while we prepare by doing something fun or rewarding. What is considered fun or rewarding are those activities that we get some sort of happy chemical rush in our brains.

The second component, and what perpetuates the procrastination, is associating negative feelings to the task we need to complete. For example, writing an essay can be boring but often has a grade attached to it, and so we’re pressured to do our best. If the subject of the essay is something we feel confident in and is of interest to us, we will be less likely to procrastinate . But, if the essay subject is not interesting and there is a potential for us to get a bad mark on it, our mood can be lowered when thinking of that end result. So, we find ourselves on social media checking out our friends’ vacation photos instead.

As this process progresses, we become aware that we are procrastinating and our self-esteem begins to take a hit. We might start to feel self-conscious or insecure about our abilities, the task in front of us might seem larger than it realistically is, and so we might look to regulate our moods by switching to easier tasks that can be done quicker. For example, I honestly do go and do the dishes when I need to feel better because the happy chemicals from seeing a clean sink are wonderful.

The final stage of procrastination is crunch time, where most of us procrastinators find ourselves finishing a task mere hours before the intended due date or just afterwards. It’s at this stage where the stress of the procrastination has eclipsed the initial feelings of boredom connected to the task. We drive ourselves on not because we are enjoying the task, but for many people because we don’t want others to associate us with being untrustworthy, unreliable or other negative associations.

Procrastination a very human trait, and something we all do to greater or lesser degrees. There are some specific mental health conditions related to mood such as bipolar disorder, depression, anxiety, eating disorders and so on, have been linked to procrastination because of the mechanism of avoidance behaviours. Likewise, emerging studies prove a link between procrastination and neurodivergence, especially ADHD. While procrastination is something everyone deals with in some form, studies around ADHD specifically show that procrastination is linked with inattention and is often a coping mechanism to regulate the boredom that comes with activities that are not stimulating enough.

So, what can we do to help ourselves?

Understanding that procrastination is often about mood and not willpower is the first step. Understanding what our coping mechanisms are and how our brains reward us with the happy chemicals can help us understand the roots of our procrastination in the first place. For example, when faced with a task we find unpleasant, take stock of what about it bores us and schedule specific breaks with rewarding activities.

Another key piece here is to understand how we conceptualize tasks and the time they take. For example, as a neurodivergent person who is a visual learner, I need to break down tasks in a visual format to understand their flow. How that looks is a white board with coloured post-it notes to represent each task, with sections for incomplete and completed tasks. I reward myself when I am able to move a post-it over to the completed section.

Environment has a lot to do with our ability to procrastinate, so find a space that works for you. For example, I find I do my best work when I am in a public space like a library or coffee shop where there is background noise but I’m not in a space I can casually procrastinate. So, I often play a YouTube video with background ambience of a café or a windy Scottish cottage and take a few moments to practice a visualization.

A huge piece ultimately to motivate us in the future is to deal with the negative self-talk when we are in crunch time. For me, I fear being seen as untrustworthy, unreliable, and incompetent. How I help myself when I begin to succumb to those fears is to remind myself of my accomplishments and accumulated success.

There is an abundance of resources out there to help understand your patterns and to address the underlying causes of procrastination. I recommend Solving the Procrastination Puzzle by Timothy A. Pychyl for more help with procrastination.

Leave a Reply