At the end of August, a tweet went viral around the Waterloo Region.

A mother of two vocalized the struggles of making ends meet, in a region that seems to be exploding exponentially when it comes to its housing markets value, but leaving behind its citizens who have not had the privilege to experience the same type of growth.

The tweet broke down the expenses that most families with children have to manage — daycare, clothing, insurance, groceries, and more.

However, the most striking note in this series of tweets was the pricing that this Twitter user had mentioned: $1,800+ per month for a two-bedroom apartment in the Region, of course, this excludes utilities.

For many in the Region, it is becoming increasingly difficult to make ends meet.

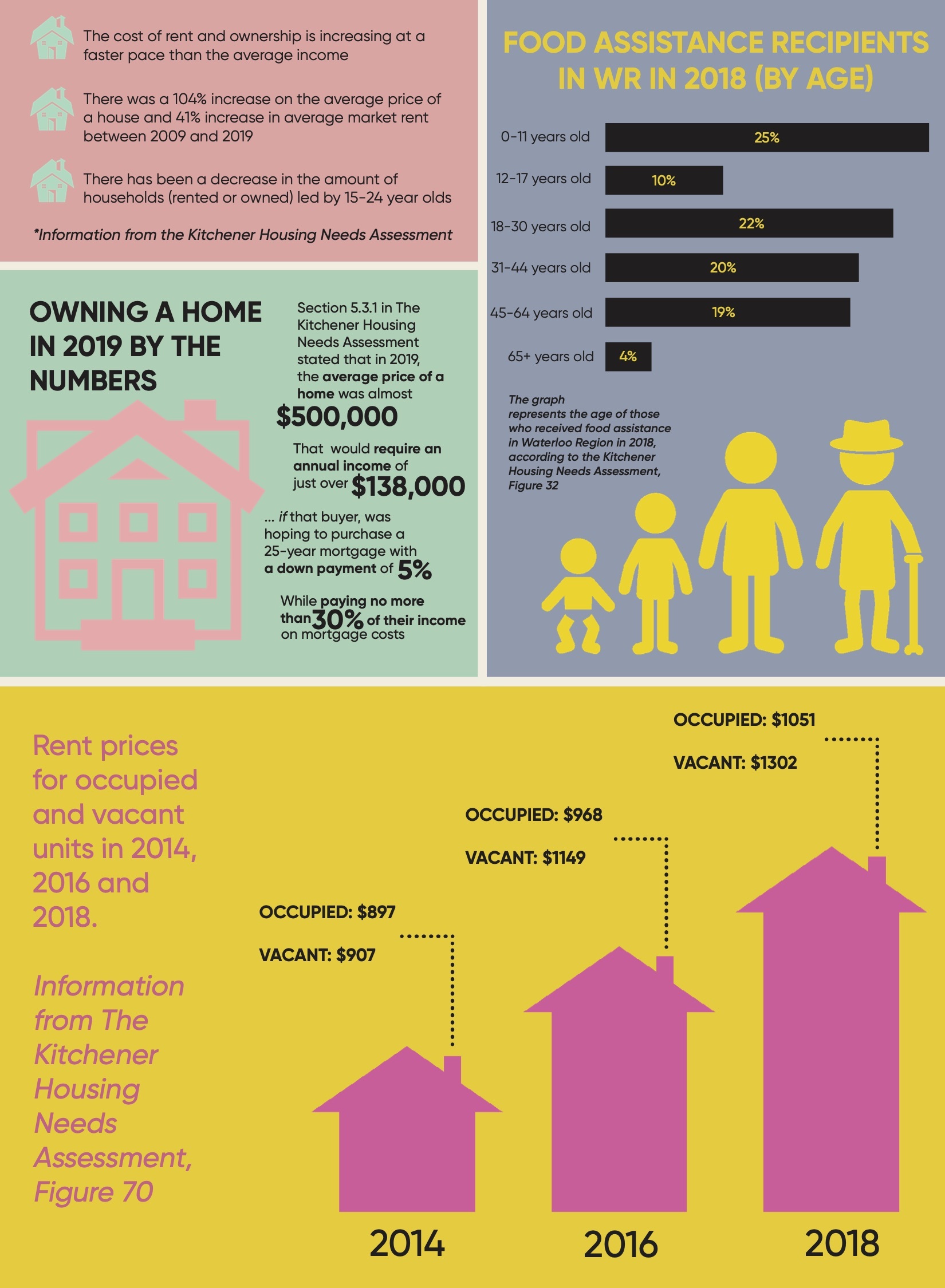

The City of Kitchener Housing Needs Assessment indicated some stark numbers in January of this year. Between 2009 and 2019, the average price of a house in Kitchener increased by 104 per cent, and the average cost to rent an apartment went up by 40 per cent. According to the same report, most of the increase for rent and homes in this period took place between the years of 2016 and 2019.

Kitchener Centre MPP Laura Mae Lindo expressed her dismay for the current affordability crisis in the Region in a recent statement.

“The Waterloo Region is fast becoming an unaffordable place to live for everyday families and young people. The cost of renting is soaring, putting even more strain on household budgets during the pandemic, and tenants are living in constant fear of above-guideline rent increases … It’s almost impossible for renters to save for a down payment on their first home.”

The Housing Needs Assessment also indicated that the use of food banks has increased. Single people using food banks has doubled since 2014, where the number was once 25 per cent, it is now 49 per cent.

Visible homelessness has increased in Kitchener as well. The Housing Needs Assessment indicates that “youth are a growing part of the homeless population.”

Lindo indicated her concern about the state of affordable housing, saying “chronic underfunding of affordable units and a lack of increases to minimum wage that just don’t keep up with inflation are the root cause of the affordability crisis in Waterloo Region and in this province.”

Survey data on the use of shelters revealed that between 250-750 supportive housing units are needed to meet the needs of people experiencing homelessness.

Moreover, there are approximately 3,750 households on the waitlist for community housing in Kitchener, and over 3,000 new units (on top of the already 4,500 existing ones) are needed to meet the needs of community members.

It is clear that there is a housing crisis in our city. But how did we get to this point?

The housing continuum is diverse and represents so many different members of the Kitchener community.

To understand why the Region has experienced such growth, I spoke with Colleen Koehler, president of the Kitchener-Waterloo Association of Realtors.

“Prices have been on the move, not just this year, but since about 2017,” Koehler said. “That’s when we started to see a demand … and it really was attributed to out of town buyers.”

Koehler mentioned factors such as the Region’s new LRT line, the strong tech sector, and the Region being a “progressive place overall” to live as a reason that buyers, especially ones from the GTA, are moving west.

Although increased value of homes in the market may be positive for current homeowners, it makes it difficult for new buyers to enter the market now.

With rent prices up by 40 per cent in the last ten years, affordable renting is often challenging for many community members, including students and youth, Indigenous people, single parents, recent immigrants, and people earning minimum wage.

Andrew Ramsaroop, the engagement and program manager for the Housing Strategy, commented on the current situation.

“The market wasn’t providing the right types of housing along the continuum, and in particular, there are gaps on the left side of the continuum, and that’s where you see homelessness, transitional housing, community housing and supportive housing,” Ramsaroop said.

Ramsaroop also noted that although prices for housing are going up, wages are not. This could explain the reason that 42 per cent of renters spend 30 per cent of their income on housing.

As mentioned by Ramsaroop, there are significant gaps on the left side of the housing continuum.

Jessica Bondy, housing director at House of Friendship, commented on the increase in demand and usages of the services provided by House of Friendship in recent years.

“Within the past number of years, we’ve really seen an increase in demand for our supportive housing, and waitlist numbers, but also in the volume and the type of people that we’re serving in our men’s shelter,” Bondy said.

“Many of the men that we serve are navigating complex mental health issues, trauma, addiction, and are just trying to survive every day.”

Bondy noted a serious need for more people to be served through the emergency shelter system as well.

“The length of the stay is now longer because the housing affordability and the housing … isn’t available in Kitchener and Waterloo.”

The same issue of prolonged stays is prominent in the supportive housing system as well.

Bondy recounted a story about a woman that she had worked with the supportive housing system.

“One of our supportive housing tenants had lived with us for seven years, and she is well past her recovery from homelessness. She’s at the point where she is thriving in her community, she’s been able to engage in the workforce. She has a partner and would one day like to have a family. This individual is eager and willing to move out of supportive housing, but because of the subsidy she is receiving, and because of the lack of availability, it has taken her two years to find a place.”

Not only is the demand for supportive housing increasing, but the transition from supportive housing to “forever homes,” as Bondy likes to call them, is backlogged because of the unaffordable renting market.

This is leading to less turnover in the supportive housing system, and more people in need of a roof over their head.

Although many of the actions which are part of the City of Kitchener’s Housing Strategy are long term, there are some actions that are going to be taken soon to address the ongoing housing crisis.

The Aug. 31, report from the Special Council meeting for the Housing Strategy listed four “Quick Wins,” actions that will be taken to improve affordability.

These quick wins include: “addressing homelessness, creating an advocacy plan, confirming housing needs and numbers and implementing an interest-free deferral of development charges, payable over 20 years for certain affordable housing projects.”

While there is much work to be done when it comes to making our region a more affordable place for everyone, Jessica Bondy remains positive.

“The people in our region care about each other, they want to make sure that our neighbours and friends and our colleagues have and can create a life here in our community.”

Leave a Reply