When some people die, their bodies are cremated. Some are buried, planted under trees, made into tattoo ink or shot into space. Some end up in the University of Waterloo’s anatomy lab, a modern building of bright whites and faded greys and blues. Inside this new building, which feels like a hospital-in-an-airport, students dissect and study the human body under the steady guidance of Jeremy Roth, senior anatomy demonstrator, and, on a cold Wednesday morning, my tour guide.

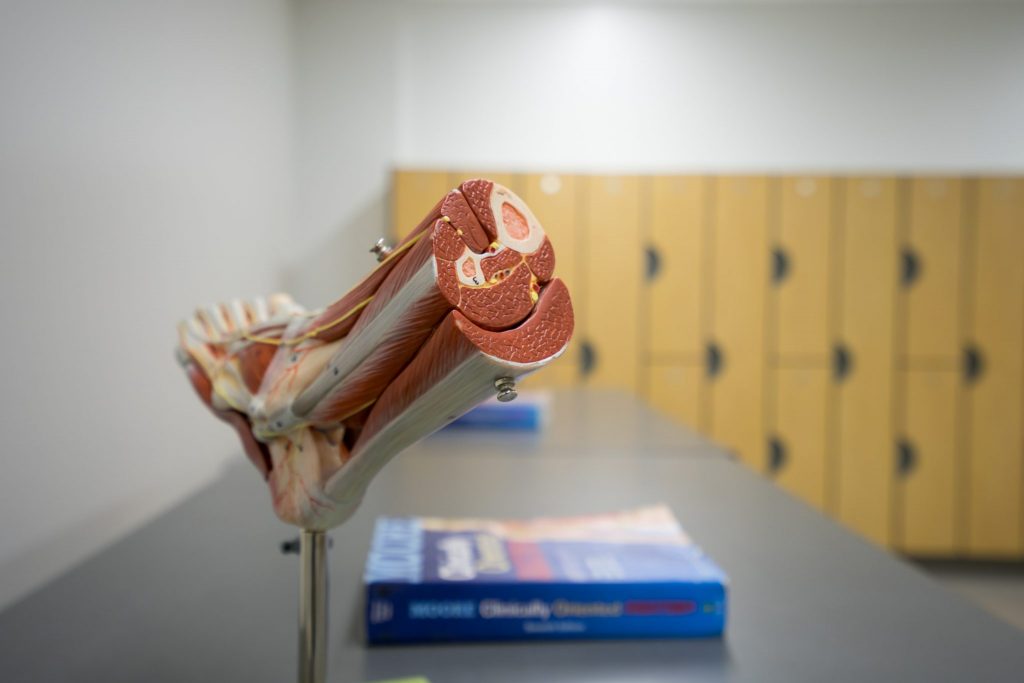

After greeting Roth I take a seat at the back of a lecture hall filled with 350 students. Roth’s lecture about the gluteal region – what parts look like, where they are, how they function – is a flurry of inferiors, superiors, and pear-shaped pieces (the piriformis, as I learned).

At times, he acts out the movements, showing the kind of activity that is going on inside him by the illustrations on screen. I rotate my leg as I sit, marvelling at the fact that I cannot feel the individual moving parts – the Latin-tongued quadrates and pears inside of me. I cannot tell them apart, cannot feel anything other than the whole.

The students around me, who have spent hours in the lab, drink coffee, jot notes and roughly sketch out the musculature into their courseware. Hundreds of bundles of muscles, bones and nerves meticulously pieced together to think about themselves.

After the lecture, Roth and I head upstairs to the third level, where the lab is located. I am somewhat surprised that it is not hidden away in a dark basement. He informs me that the old anatomy lab, located across the street in the Optometry building, fit that image. He does not remember it fondly. We both dress in white lab coats (Roth’s name is emblazoned on each of them) and enter a large, highly organized, brightly lit room with multiple metal gurneys, four of which are covered in white body bags. At first I am taken aback by the sheer immediacy of it all: we have moved from an office-like work station into the presence of the dead. That feeling quickly gives way to utter fascination, and as we walk about the room he describes the process that each of these four bodies underwent before ending up in the anatomy lab.

We both dress in white lab coats (Roth’s name is emblazoned on each of them) and enter a large, highly organized, brightly lit room with multiple metal gurneys, four of which are covered in white body bags. At first I am taken aback by the sheer immediacy of it all: we have moved from an office-like work station into the presence of the dead. That feeling quickly gives way to utter fascination, and as we walk about the room he describes the process that each of these four bodies underwent before ending up in the anatomy lab.

When death occurs, the deceased’s executor contacts the school within 24 hours.

“We work with the families quite closely at the time of death,” Roth tells me, adding that family members are aware of the deceased’s wishes. “If we think that not everyone in the family is on board, we won’t accept the donation.”

Upon learning of the death, a screening process begins. Some medical cases rule out accepting a body, and sometimes the body is too large or tall to be adequately stored. There is only so much space in such a small program. A funeral director embalms the bodies on site, but because “you can’t embalm a body that isn’t a closed system,” Ontario schools will only accept full body donations.

Bodies, by law, can be kept up to three years, but the University of Waterloo usually keeps them for two. After two years families are contacted for permission to keep certain parts of the body for further study. If they allow it, the body is examined and any specific parts that can be used – a knee joint, or a hand, for example – are removed before cremation. Otherwise the body is wholly cremated and the remains returned to the family. The process, from start to finish, is dictated by the Anatomy Act of Ontario and the Human Tissue Gift Act, renamed the Trillium Gift of Life Network Act in 2000, but also by respect and attention to the emotions of the situation.

The process, from start to finish, is dictated by the Anatomy Act of Ontario and the Human Tissue Gift Act, renamed the Trillium Gift of Life Network Act in 2000, but also by respect and attention to the emotions of the situation.

“You are now in the presence of those who have given their bodies for the advancement of science. Please treat them with the respect which is their due,” reads a quotation by the entry doorway to the lab, spoken originally by the School’s founder.

Roth’s behaviour emanates respect. His touch is delicate as he carefully unzips the outer and inner white body bags and folds back the moistened material used to keep the body from drying out. He takes the opportunity to further his lecture, as the cadaver we observed was in a position that allowed us to more closely examine the gluteal region. The powerful position these donors hold permeates the lab. In a society that tends to hold death at a distance this gift is particularly meaningful, continuously contributing to our understanding of science and of ourselves. The donors relish this opportunity – to help new students learn, to instill a sense of awe and respect for the complexity that is the human body. It is impossible to ignore Roth’s sincerity in this moment.

The powerful position these donors hold permeates the lab. In a society that tends to hold death at a distance this gift is particularly meaningful, continuously contributing to our understanding of science and of ourselves. The donors relish this opportunity – to help new students learn, to instill a sense of awe and respect for the complexity that is the human body. It is impossible to ignore Roth’s sincerity in this moment.

“It sucks, when you can’t [accept a donation]. When we’re full and you have to talk to someone whose loved one wanted to donate their body and we can’t? It sucks,” he says.

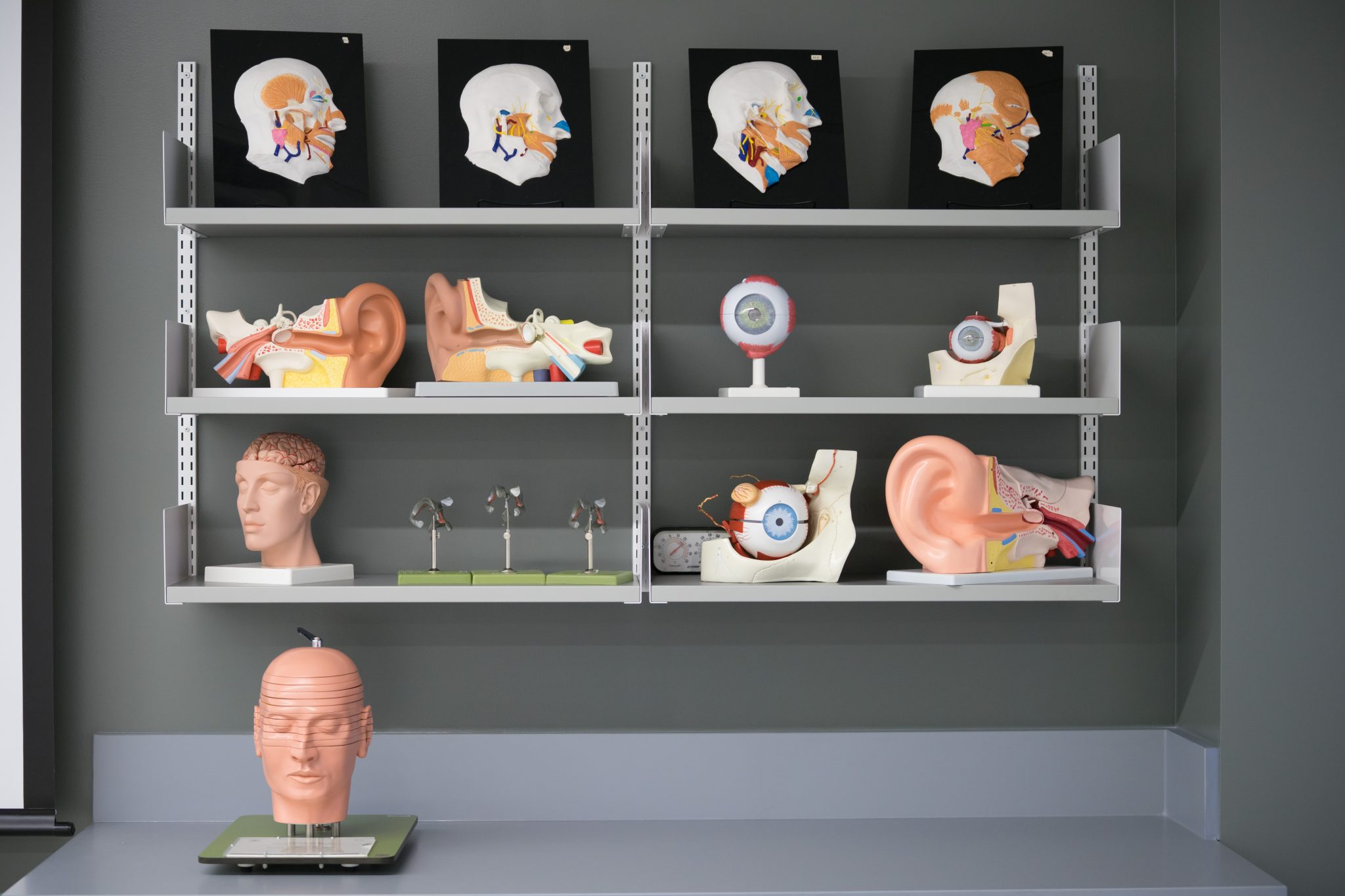

The students begin pouring in at the end of the tour, preparing themselves for the lab ahead. They all look professional and eager to get to work. Roth guides me through a small hallway that he refers to as the “art gallery,” which is decorated by art made by fine arts and kinesiology students. The pieces are beautifully done, some in black and white, some in full colour. Some are so detailed that they could be used in study.

Roth points to one, showing a row of five butterflies. The second from the right, however, is actually the sphenoid bone, located in the skull. It is probably the most representative artwork of the whole drive and purpose behind the anatomy lab – to observe the world as it is, and understand all of the moving parts within. It is a somewhat comforting thought that in our heads there is a bone that looks like a butterfly.

Leave a Reply