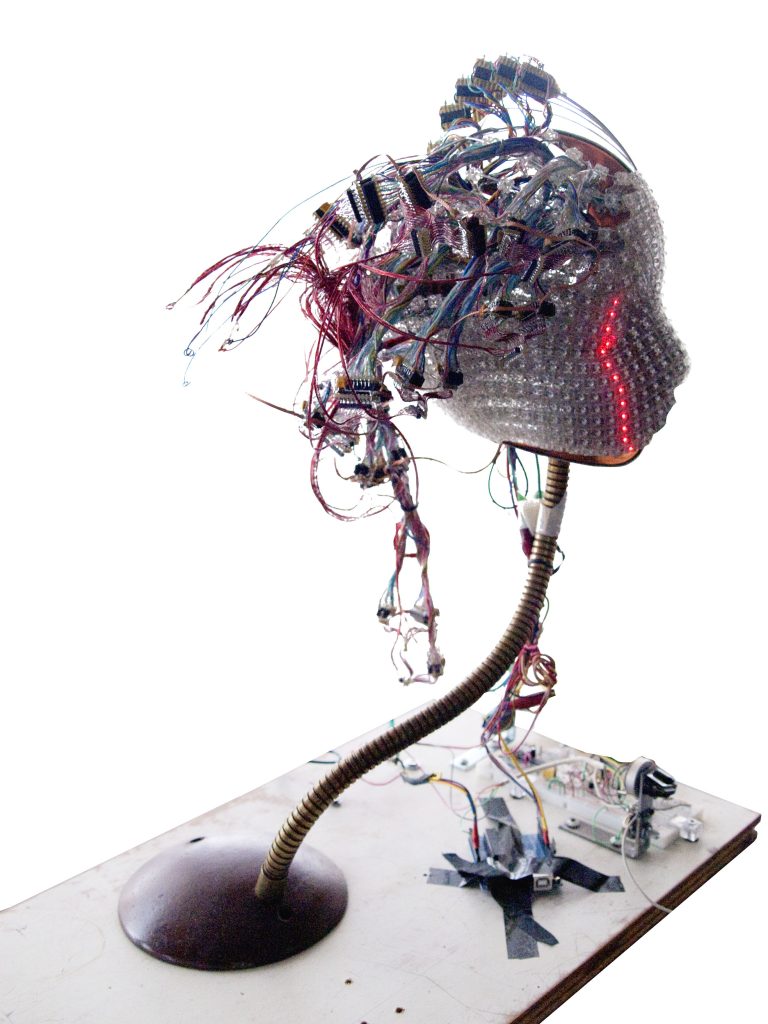

Who says an exquisitely well-written program isn’t art…

Artists and counterculture members seek each other out for community and creativity naturally. It’s why the Impressionists splintered off from the French art establishment and why Greenwich Village and San Francisco are still known for being “alternative” — even if today they are mostly filled with expensive condo towers.

Hacklabs have a similar history, though many of the movement founders may not necessarily call themselves artists in the normal sense of the word. It begins in Germany, where a tradition of squatters’ rights and a plethora of abandoned warehouses meant people could set up shop wherever they pleased. One of the first such spaces to gain notoriety was c-base established by the Chaos Computer Club, a Berlin-based network of hackers. Their original focus did seem more in tune with what the public perception of hackers was — in 2008 they obtained the fingerprints of a German politician and published them to protest biometric data collection — but the way CCC combined art and computers laid the ground work for the labs that followed.

The idea of hacklabs began to slowly make its way over the Atlantic, with spaces popping up in New York City and San Francisco. A recent New York Times article estimates the amount of hacker spaces in 2012 to number around 200, with some cities supporting several spaces within their limits.

In southern Ontario, labs are set up in Guelph (Diyode), London (The unLondon Hack Lab), Hamilton (Thinkhaus), two in Toronto (site3 and hacklab.TO), one on the way in Windsor and of course, Kwartzlab in Kitchener. The core Kwartzlab group began planning the idea in 2009, and in six short months moved into the space they now call home.

It’s tricky to sum up exactly what it is a hack lab does. The best way to describe it is simply: whatever it damn well wants to. “The people are smart and willing to experiment,” says Richard Degeleer, the president of Hamilton lab Thinkhaus. The only thing really limiting anyone is their own limitations — and of course, space and money.

“The spaces reflect the people who run them,” says Degeleer. “They also reflect the real estate.” Site3 in Toronto is on the second floor of a house in the Kensington Market neighborhood market, which means the space can’t do the same kind of projects that can be done in a large ground floor space like Kwartzlab.

“These are people who don’t just sit around and talk about the awesome things they could do, they actually do it,” says Terre Chartrand, a former artist-in-residence at Kwartzlab.

Chatrand’s a jack-of-all-trades who writes plays and designs the occasional tattoo. For her, art isn’t as black and white as what may appear in a gallery. “It’s people who get their hands into things and make things by hand,” says Chartrand. “Who says an exquisitely well-written program isn’t art?”

There’s a definite sense that this is a place where anyone is welcome to come play and create. One member’s kids are playing in another area, and some even get to work on projects. On the night of my visit, Chartrand and myself are the only women present, but Cassleman estimates that female membership sits at around 30 per cent.

“[Female representation in] tech in general is usually around 18 per cent,” says Chartrand, noting that Kwartzlab is doing fairly comparably. Both stress that diversity is key to a truly lively space.