Neighbours have rallied to push back against one of the shiny, new developments that are sprouting in Kitchener, Waterloo and Cambridge.

In Kitchener’s Mount Hope neighbourhood, residents say they can live with the plan to build a 50-metre office building, but oppose a five-storey parking garage that they worry will loom over nearby backyards.

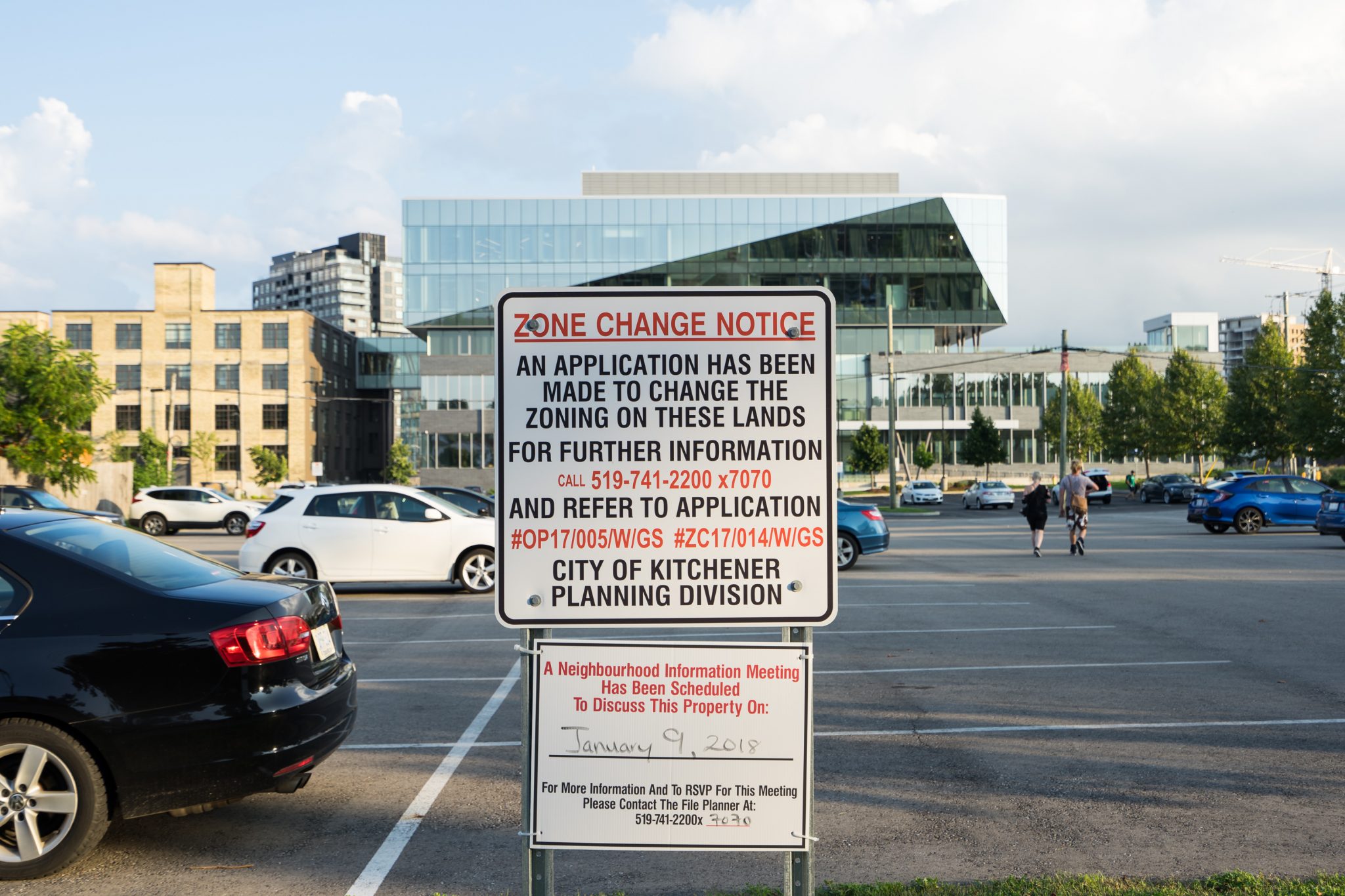

The project adds 10 storeys of prime office space and new stores on the ground level to the neighbourhood which is bordered by Victoria, King, Union and Weber Streets. The property is currently a parking lot on Wellington Street and Moore Avenue, next to the Google building on King and Breithaupt Streets and just steps from the new LRT tracks and Waterloo Region’s future transit hub.

This is Phase 3 of the Breithaupt Block project, which has already seen Perimeter Development transform a derelict factory from an eyesore into the tech giant’s headquarters.

To Perimeter and the City of Kitchener, it’s a prime spot for more intensification. But neighbours who feel the project is too big and too close to their quiet streets and historic homes filed legal appeals this summer to stop it. Passionate arguments at Kitchener city council and committee meetings in April and June didn’t stop the plan’s approval, but volunteers aren’t giving up. After feeling ignored and disillusioned by the city process and decision earlier this summer, neighbours are now hoping Ontario’s independent Local Planning Appeals Tribunal (LPAT) will listen more closely, said Dawn Parker, a professor at the University of Waterloo’s School of Planning, as well as a Mount Hope neighbourhood member involved in the efforts to challenge the development.

To Perimeter and the City of Kitchener, it’s a prime spot for more intensification. But neighbours who feel the project is too big and too close to their quiet streets and historic homes filed legal appeals this summer to stop it. Passionate arguments at Kitchener city council and committee meetings in April and June didn’t stop the plan’s approval, but volunteers aren’t giving up. After feeling ignored and disillusioned by the city process and decision earlier this summer, neighbours are now hoping Ontario’s independent Local Planning Appeals Tribunal (LPAT) will listen more closely, said Dawn Parker, a professor at the University of Waterloo’s School of Planning, as well as a Mount Hope neighbourhood member involved in the efforts to challenge the development.

The neighbours want a smaller parking garage and more green space around the buildings. There are also concerns about increased traffic and disruption from the building’s loading dock.

Many people in the neighbourhood want small tweaks rather than wholesale changes, Parker said. The community is actually excited about new shops or cafes that might appear on the ground floor. Perimeter Development did agree to address neighbours’ concerns about height by reworking their design this spring to lower the office tower by two storeys — although the building’s total square footage didn’t decrease and the parking garage was unchanged.

That was a successful compromise, but other neighbourhood requests seem to have fallen on deaf ears, Parker said.

“I think we’re being eminently reasonable,” she said. “I think minor changes could make this a good development.”

The city isn’t able to comment on a case that’s currently under appeal, said Alain Pinard, Kitchener’s Director of Planning.

But, as a whole, the LRT project has created a development spike that is helping transform the city, he said.

Intensification often prompts a passionate response, he noted. Almost everyone agrees that a more efficient, walkable city is best.

“But there’s no consensus on how much intensification is appropriate and where it should go,” Pinard said.

The city tries to balance the views and the rights of both developers and nearby residents. In the end, someone usually won’t get what they wanted, Pinard said.

But many neighbours who attended the marathon, three-plus hour council sessions this spring and summer that ultimately approved the BB3 project felt disillusioned by the appearance that city staff and council members weren’t open to any of their suggested changes, and wonder why the city couldn’t help them achieve more compromises.

“With this development, they’re not being held to the same standards that others are,” Parker said — developers often have to incorporate affordable housing or parkland to get city approval.

“When the developer says he did everything that was asked of him, he’s correct. And that shouldn’t have happened.”

The Mount Hope residents seem to have decided not to accept this development project without voicing their concern one more time.

The neighbourhood, which has built a strong connection over the years with regular potlucks and street festivals, has focused that communal energy into figuring out the new LPAT process.

Volunteers raised money, wrote their case, and have filed paperwork for two appeals this summer against the city’s decision to allow the Breithaupt Block 3 plan.

The Local Planning Appeal Tribunal (LPAT) still has to decide if the neighbour appeals are valid, then in the coming year the case could move to a hearing. If that happens, the neighbourhood will need to mobilize again to find experts and presenters to make their case.

The decision-makers in municipal government take all public input very seriously, Pinard said, but the neighbours are only one point of view that must be balanced against other factors.

“In no case do we not listen to community comments,” he said. “We try to develop solutions to address concerns. But at times we do not get there.”

The amount of change possible also depends on the developer’s willingness to compromise, he added, and the city planners have worked extensively on the developer’s plan before the public gets involved.

With limited room left for Waterloo Region’s cities to sprawl and the desire to densify along the LRT, more conflict between other established Waterloo Region neighbourhoods and ambitious developers could be on the horizon.

Not everyone who spoke up or gave money to fund the LPAT appeals is a Mount Hope resident; this Breithaupt Block project has also attracted people from other Kitchener neighbourhoods who are worried about the precedent this case might set for future projects.

“We’re seeing these kinds of issues popping up all through the core neighbourhoods,” Parker said. “They can see others coming down the pipeline, they want to protect their stable neighbourhoods.”

If the City of Kitchener allows this sort of incongruent building here, it’ll have a harder time turning down other developers with similar ideas in the future, she worried.

Every development project is considered independently, Pinard said, depending on the characteristics of the community, like its proximity to downtown or the train line.

“All neighbourhoods are different,” Pinard said. “There isn’t really a one size fits all when it comes to developing the tools or the approach to intensification.”

Kitchener has long wanted to see this sort of transformation and growth in its downtown and central neighbourhoods, Pinard continued.

“It’s exciting to be a part of this and help shape it,” he said, “and it’s a challenge because there are people with competing views on exactly how it should be done and how fast it should be done.”

In the end, the city and the neighbourhood have very similar goals and agree on a lot, Parker said. But the neighbourhood didn’t feel their voices were given an equal seat at the bargaining table. It was an emotional rollercoaster, Parker said, to put in so much work and feel that the city didn’t respond.

Neighbours have spent unpaid hours to make their voices count in their community’s future.

“It’s because the neighbourhood was so well connected that they were able to rise to this challenge,” Parker said.

Mount Hope has turned its neighbourly spirit into a grassroots political campaign. Other neighbourhoods may soon follow suit.